By Staff Reports

(Hawaii)– A collaboration between researchers at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), Hawai‘i Pacific University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) revealed for the first time growth rates of deep-sea coral communities and the pattern of colonization by various species.

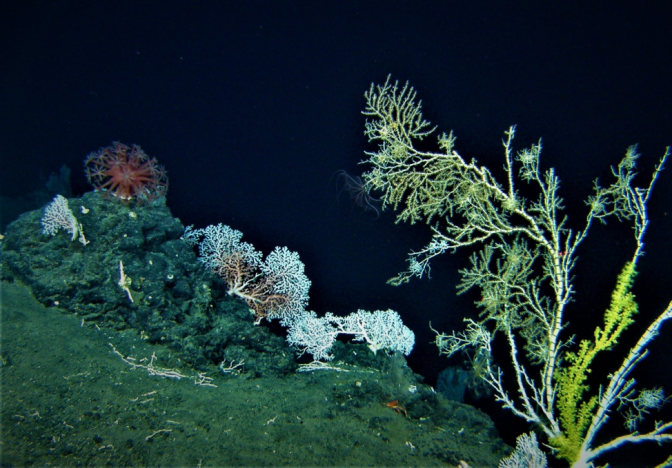

The scientific team used the UH Mānoa Hawai‘i Undersea Research Laboratory’s submersible and remotely-operated vehicles to examine coral communities on submarine lava flows of various ages on the leeward flank of the Island of Hawai‘i. Utilizing the fact that the age of the lava flows—between 61 and 15,000 years—is the oldest possible age of the coral community growing there, they observed the deep-water coral community in Hawai‘i appears to undergo a pattern of ecological succession over time scales of centuries to millennia.

The study reported Coralliidae, pink coral, were the pioneering taxa, the first to colonize after lava flows were deposited. With enough time, the deep-water coral community showed a shift toward supporting a more diverse array of tall, slower growing taxa: Isididae, bamboo coral, and Antipatharia, black coral. The last to colonize was Kulamanamana haumeaae, gold coral, which grows over mature bamboo corals, and is the slowest growing taxa within the community.

“This study was the first to estimate the rate of growth of a deep-sea corals on a community scale,” said Meagan Putts, lead author of the study and research associate at SOEST’s Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research. “This could help inform the management of the precious coral fishery in Hawai‘i. Furthermore, Hawai‘i is probably the only place in the world where such a study could have been performed due to its continuous and well known volcanology.”

“Prior to beginning this work, it was unclear if a pattern of colonization existed for deep-sea coral communities and in what time frame colonization would occur,” said Putts. “When put into context with what we do know about the life history of Hawaiian deep-water corals, the results of this work make sense.”

The fastest growing species with calcium-based skeletons, a ubiquitous building material in the deep ocean, Coralliidae, were the first to colonize and in the largest quantities. Corals with protein-based or partially protein-based skeletons, were seen later in the colonization timeline because the formation of proteinaceous components requires organic nitrogen, a much more limiting resource in the deep sea. Gold coral, Kulamanamana haumeaae, also has a protein-based skeleton but was the last species to be seen within the patter of community development because it requires a host colony of bamboo coral to present and of a large enough size for colonization.

This study has important conservation and sustainability implications regarding these ecosystems that had never before been ecologically quantified. This research also provides insights about recovery of deep sea ecosystems that may be disturbed by activities such as fishing and mining.

“Further,” said Putts, “as the Island of Hawai‘i continues to have periodic eruptions producing very recent deep-water lava flows, the last in May 2018, there are opportunities to study initial settlement patterns and appraise the impact hot, turbid, mineral-rich water from new flows has on coral communities.”